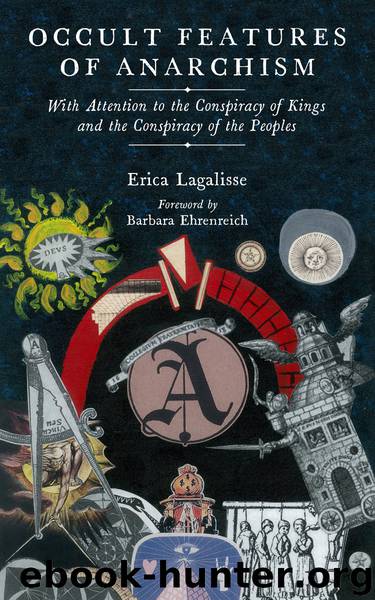

Occult Features of Anarchism by Lagalisse Erica; Ehrenreich Barbara;

Author:Lagalisse, Erica; Ehrenreich, Barbara;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: PM Press

Published: 2019-01-15T00:00:00+00:00

1 See Glenn Alexander Magee, Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 212.

2 From Bruno’s Italian Dialogues, cited in Frances Yates, The Art of Memory (London: Routledge, 1966), 228.

3 Paolo Rossi, Logic and the Art of Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), explains how Descartes, Liebniz, and Bacon honored a correspondence between words (termini) and things (res) (chapter 5; see also 61, 114, 191) and how Ramus proceeds similarly yet differently (98–99, 101). The direct quotes from Ramus are taken from Yates, Art of Memory, 233, and refer to P. Ramus, Scholae in liberates artes, Scholae rhetoricae (1578), providing discussion (231–42). Bruno called Ramus a “pedant,” associating Ramus’s interpretation with the Greek tradition, as opposed to his own, which was inspired by the spiritual insights of the Egyptians; see Yates, Art of Memory, 272. Yates suggests that Giulio Camillo started a historical-methodological-memory movement that Ramus rationalized by omitting images (239–41).

4 See Brian Copenhaver, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 33, 56; Georg Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977 [1807]). In Yates’s discussion of the Asclepius (Corpus Hermeticum II) in Art of Memory, she likewise elaborates on the question of recognition in the Hermetica: “When God created the second god, he seemed to him beautiful and he loved him as the offspring of his divinity … but there had to be another being who could contemplate what God had made and so he created man” (36).

5 See Georg Hegel, The Science of Logic, trans. George Di Giovanni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010 [1812]).

6 Regarding the monism (vs. dualism) of Hegel’s philosophy, see, e.g., Frederick Beiser, Hegel (London: Routledge, 2005). Regarding Hegel’s relationship with Freemasonry, see Susan Buck-Morss, “Hegel and Haiti,” Critical Inquiry 26, no. 4 (2000).

7 See Robert M. Cutler, ed., Mikhail Bakunin: From Out of the Dustbin: Bakunin’s Basic Writings, 1869–71 (Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis, 1985) for further discussion, especially 18–21, (quote is on 21, author’s emphasis).

8 Here I follow Carl Levy, “Anarchism, Internationalism and Nationalism in Europe, 1860–1939,” Australian Journal of Politics and History 50, no. 3 (2004).

9 Bakunin cited in Sam Dolgoff, ed., Bakunin on Anarchy (New York: Random House. 1972), 199; Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” in The Marx-Engels Reader, ed. Robert C. Tucker (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1978 [1852]).

10 Engels in letter to Cuno, cited in Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism, 1864–1892 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 53; Bakunin cited in Pernicone, Italian Anarchism, 47.

11 Bakunin cited in Cutler, Mikhail Bakunin, 21.

12 See Carl Levy, “Anarchism, Internationalism and Nationalism in Europe, 1860–1939,” Australian Journal of Politics and History 50, no. 3 (2004): 331. For further analysis of the rivalry between Marx and Bakunin in the IWA, see Julius Braunthal, History of the International, vol. 1, 1864–1914, (New York: Frederick A. Praeger Publishers, 1967); Wolfgang Eckhardt, The First Socialist Schism: Bakunin vs. Marx in the International Working Men’s Association (Oakland: PM Press, 2016).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anarchism | Communism & Socialism |

| Conservatism & Liberalism | Democracy |

| Fascism | Libertarianism |

| Nationalism | Radicalism |

| Utopian |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18163)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11954)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8452)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6440)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5832)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5494)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5357)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5239)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5017)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4958)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4908)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4859)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4691)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4551)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4545)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4389)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4381)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4324)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4246)